Our Community Writer in Residence, Eleanor Thom, reflects on her first year working with Edinburgh residents on Citizen.

‘The pattern was just a human one’

Working in North Edinburgh, Wester Hailes, and Liberton this year, I encouraged a lot of people to write their autobiography in just five randomly selected moments. I think you can communicate the essence of yourself, where you’re from and who and what matters to you, in relatively few words. The selection itself is always revealing.

With that philosophy in mind, here are five moments (in no particular order) representing my first year working on Citizen and with its many wonderful participants.

April

There were twenty-five pupils in my Thursday group. That was a lot, especially at 3:30pm when more than anything they wanted to chat and snack and run around, but I’d visited enough times already that I knew something about every child. I’d learnt which one collected squishies, which one was obsessed with Land Rovers, which one was learning the violin.

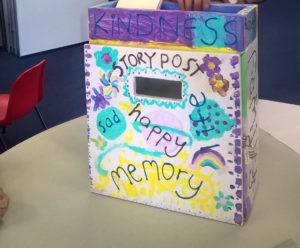

The week before, they had painted a wooden rectangle and frame that I’d taken home, coated with sealant, and screwed together. Now it was the Citizen Post Box. It would travel from here to an arts centre, to another school, and then to the Book Festival in Charlotte Square, collecting stories from everyone. On top of the post box there was a shelf with blank cards and pencils.

There had been squabbles over the design: flowers, planets, rainbows, or alternating squares of colour? In the end they went for a mixture of everything. And later, split into two groups, they had chosen the words to be added after the paint had dried: happy, sad, family, friendship, memory. These were things they associated with being citizens and telling stories.

They liked the blank cards and sharp new pencils, and they liked posting their stories in the slot. One girl asked if she could write down a quote, and how to spell some words. Like many others in this group, I knew she had learned another language before English.

At the end of the afternoon I sat in the car watching the kids walking home. It was still cold and I wondered what it had been like for the girl to move here from a warm country, adapting to such long winters. I looked through the posted stories for her quote. It took a minute to find because ‘quote’ was spelled ‘coat’. Accidental poetry. I imagined the girl wearing this coat, a big sheepskin duffle, buttoned up for protection.

A Coat: You are not ugly. Go into the world and live your life!

January

When a member of the Knit and Natter group lost a loved one on Christmas Day, the group rallied for her. They had worn purple to the funeral the day before, per her wishes, and today every single knitter appeared wearing purple still. They knitted quieter than usual, sips of tea and needles ticking time, and they understood what to say to make each other laugh. Between the home bakes and the balls of wool, crocheted butterflies spilled over the table in shades of violet and mauve.

August

The invitation was illustrated like a little zine, inviting me and my husband Chris to Charlotte Square Gardens on the first night of the Book Festival. There was a live band and a big crowd. I didn’t know anyone, but some faces looked familiar and I wondered if I’d seen them on television. Ann and Karmen would be here somewhere. They were from my group, the writers from North Edinburgh, one third of a tribe that I felt I belonged to.

Since February we’d been meeting in Muirhouse Library every Tuesday morning for tea, coffee and a sharing of biscuits. Karmen liked the chocolate ones best. We’d write, tell stories, talk about books, films, street art, Anne’s knitting, hospital appointments, life’s ups and downs.

Write with people and fairly soon you’ll feel yourself belonging to something or somewhere. That’s always been my experience, and by now I felt I firmly belonged to the Tuesday morning writers’ group.

Ann and Karmen arrived with red lips and bright accessories, both wearing black. We greeted each other warmly and I felt better now. There was wine, followed by speeches, then more music. Ann did a decent flamenco dance still seated at the table, her arms twirling up and a smouldering look. We laughed. And then the band played something you could line dance to and everyone got up and jumped about for a bit.

The next song was kind of bluegrass hip-hop. Chris flipped up his hoodie, cleared himself a space and dropped to the floor. He began spinning on one knee, sped into a windmill before adopting a zany freeze-frame on his bottom. People near us were bent double laughing. They got out their phones for photos. Maybe later they would ask, who was that funny guy breakdancing?

Needing air, we escaped the noise of the tent. The four of us sat at a wooden table. Karmen smoked a cigarette and Ann relaxed into the back of her chair. We could feel the festival waiting to happen in the dark tents around us. They would soon be full of visitors from all over the world. It was late now, but earlier there had been a huge storm and the grass was wet. In ten days Ann and Karmen’s stories would be performed here, and the others in the group would be on stage too, Patricia and David and Betty. But that evening it was just good to be there first, feeling like part of it belonged to us, and listening to the fireworks over the castle and the murmur of the crowd.

February

I was finding it hard using the word ‘Citizen’ so I talked it over with Create, a group of women at Wester Hailes. What if some people associated the word ‘citizen’ with not belonging, not being accepted? That morning as I’d slung the bag of microphones over my shoulder I had worried about being mistaken for an undercover Home Office agent.

Once, when Chris and I were in Berlin, two men became furious because Chris was getting ready to record church bells from a café table. They thought he was trying to capture their conversation. “People here are sensitive about that kind of thing!” they shouted at us. For some reason the church bells didn’t chime on that particular hour, so we looked even more guilty.

There was an odd synchronicity going on for me because in the background all year I had been jumping through hoops to become a German citizen. My grandmother had been a Berliner, but I knew I was set for a rejection, and maybe an appeal.

Today the group’s conversation went in another direction. We talked about the uniforms they had worn, roles they had played, dressing up for school and later for factories making medical supplies, or for busy hospital wards. That was what it meant to them to be a citizen.

“I’ve got a story for you,” said one lady who had shied away from the microphone till now. She grabbed it with both hands. The story she told was one of my favourites that day, but it didn’t record properly. Nevertheless, the picture she painted, and her smile as she told the story, would stay in my mind for the rest of the year.

It was her first position, she said, right out of school and into the hospital laundry. There were big machines swirling and a chute like a giant hand drier that the pillowcases and sheets would whoosh out of. Her job was to stand at the chute and catch everything that came out of it. Not very interesting, you’d think, she winked. But the lost property was incredible. Remember, a hospital is a place anyone can end up. Rich and poor. So one day she was stood at the chute and some ailing person up there on the wards must have stuffed a fortune in their pillowcase. First a £1 note came out, and then another, and another. They just kept fluttering down. It was a lot in those days, she said. And just as she could imagine no greater luck than she’d already had, a crisp £20 note fell directly into her hands. It was one of the best nights out of her life, she said, a night she’d never forget.

May

North Edinburgh Arts was packed the day of the event, and the sun was warm in the garden. At the back, the wild flowers planted early in the year were starting to appear and kids were playing among them. My kids were here too, the youngest digging in the sandpit, the eldest making new friends, building things with sticks and annoying the volunteers at the barbeque, asking a hundred times when the burgers would be ready.

There were maps and illustrators and cartoonists inside, and half-way through the afternoon I sat beside the writing group in the theatre. The sound piece filled the dark room. Some of the stories made people catch their breath and everyone was listening quietly.

Projected behind the stage, the waveform stitched a ribbon of voices. This was just a selection of the people I had met since December. As I listened I could see their faces in my mind, all different people with very different stories to tell, but the waveform unified everyone. At least to my eyes, the spikes in the pattern wouldn’t reveal the gender or the age of a person, whether that person read books or didn’t, if they were rich or poor, if this was someone whose speech was impaired, or someone with an accent from north or south, or overseas. The pattern was just a human one, and beyond that it didn’t discriminate.

Share this Post