Coinciding with the broadcast of his new BBC Scotland TV series and the publication of its accompanying book Scotland from the Sky, James Crawford, publisher at Historic Environment Scotland, joins us at ReimagiNation: Glenrothes in just over a week. Here, he tells us what a view from above can tell us about Glenrothes, Scotland’s New Towns more broadly, and the nation at large. Book now to see James in Glenrothes, where you can ask your questions too: James Crawford: Scotland from the Sky

‘The architects of the past did not build for men; they built for money’

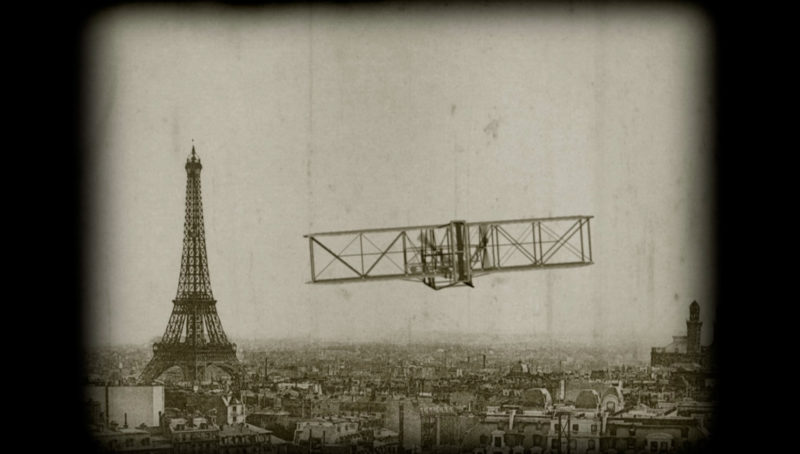

This is a story about Glenrothes that you probably won’t have ever heard before. It is an origin story, and it does not begin in Fife. In fact, it does not even begin in Scotland. It begins in Paris, on the afternoon of 18 October 1909. That day marked the first time an aircraft flew over a city.

One of the earliest pioneers of powered flight – the Frenchman Count Charles de Lambert – piloted a Wright Model A Flyer from the Juvisy Aerodrome to circle the Eiffel Tower. Watching the spectacle from the window of his garret on the Rive Gauche was another Charles – Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, a 19-year-old Swiss-French art student and son of a watchmaker. This young man would become the cultish father-figure of modern architecture: known as ‘Le Corbusier’.

Count Charles de Lambert circling the Eiffel Tower in 1909 – the first time an aircraft ever flew over a city.

From that moment on, Le Corbusier became obsessed with aircraft. He saw them as the perfect symbol of the technological future. When he finally took to the skies himself, some two decades later, he described the experience as ‘ecstasy’. At the same time, the view from above opened his eyes to what he believed was a terrible truth. ‘Fly over our nineteenth century cities’ he said, ‘over those immense sites encrusted with row after row of houses without hearts, furrowed with their canyons of soulless streets. Look down and judge for yourself . . . The architects of the past did not build for men; they built for money’. ‘We now have proof’ Le Corbusier went on, ‘recorded on the photographic plate, of the rightness of our desire to alter methods of architecture and city planning. The airplane instills the modern conscience. Cities with their misery must be torn down. They must be largely destroyed and fresh cities built.’

‘Scotland must plan, or disintegrate’

What does this any of this have to do with Glenrothes? Well, quite a lot actually. Because, in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, Le Corbusier’s message was embraced wholeheartedly by a new generation of Scottish planners and architects.

Glasgow city centre in 1947, photographed as part of a six-year-long RAF survey of all of Scotland. At that time, it was home to the most densely packed population of any city in Europe.

The human cost of the Second World War was immense, unparalleled. But so too was the architectural cost. While Scotland had avoided the brunt of the destruction, it emerged far from unscathed. Luftwaffe attacks on Clydebank had smashed the fabric of the town. There, the only option was to rebuild. But the war had also exposed the unsuitability of living conditions across the country, and in particular in the big cities. Overcrowding, squalor, poor amenities and inadequate infrastructure were the norm. Scotland’s cities were seen as things of the past, ill-equipped to deal with the demands of the present, let alone the future. As the architect John Wilson put it, ‘Scotland must plan or disintegrate’. There was an urgent need to look at the country in its entirety, assess every inch of land. And, as it turned out, the best way to do this was from the air.

In 1944, even before the war had ended, a handful of RAF squadrons were tasked with making a complete photographic map of all of Scotland. The same planes, pilots and photographers who had helped plan and carry out the bombing of Europe were now instrumental in rebuilding on the home front. They carried on for six years – over 500 flights taking nearly 300,000 photographs of Scotland (and what’s more, their photographs were in 3D… By taking multiple, top-down, overlapping images and viewing them through a device called a stereoscope, the illusion was created of depth and scale: the landscape could spring into life like a miniature scale model).

Their work effectively took planners into the sky. Mosaic maps were made from stitched together photographs – each one-metre-square mosaic corresponding to twenty-five square kilometers of real land. What could be laid on top was the blueprint for a post-war nation. The vision for a new Scotland was rising up out of these photographs. It was used to plan new hydro schemes, flooding entire valleys to bring electricity north of the Highland line. It was used to plot the locations of new forestry and farmland. It was used to redesign the chaotic, overcrowded jumble of our biggest cities. And it was used to locate and create entirely new settlements – Scotland’s New Towns.

‘The God’s Eye View’

At the centre of this image, you can see the Tullis Russell and Co. Paper Mill, nestling down beside the banks of the River Leven. The year this photograph was taken – 1948 – Glenrothes was designated as Scotland’s second New Town. Aerial photography had been used to select this stretch of rolling agricultural land as a new home for some 30,000 people.

Auchmuty High School under construction in Glenrothes, 1955

From my own experience, flying all over the country while filming the new BBC documentary series Scotland from the Sky, I can say that it is a view that is both seductive and compelling. From the air, the Scotland I thought I knew became something else. The familiar was detonated by perspective, and I could feel the arresting power of being at once distanced from and connected to the world below.

In a helicopter over Highland Perthshire with Loch Tummel in the background, while filming Scotland from the Sky.

Look down and the answers appear obvious – transform a landscape here, reshape an entire city and move a whole population there. Knock all that down. Build all this up. Of course, the reality is never quite that simple.

What we do know is that Le Corbusier refined his vision for the future in a cockpit high above a city. Which begs the question: through this ‘God’s-eye view’ did he – and Scotland’s post-war planners – gain revelatory insight, or lose track of the people they were so anxious to help, the little specks all the way down there on the ground? It is a vital question to ask of a viewpoint that has been instrumental in shaping the Scotland we know today, and is continuing to shape the Scotland of tomorrow.

Written and presented by James Crawford, Scotland from the Sky will be broadcast on BBC1 Scotland at 9pm on 16, 23 and 30 May. The accompanying book, published by Historic Environment Scotland, is out now from all good booksellers.

James Crawford is the HES Publishing Manager. Over the past decade he has researched Scotland’s National Collection of Aerial Photography – an archive of millions of images held by HES – and has written a number of photographic books on its history, origins and application, including Above Scotland, Scotland’s Landscapes, and Aerofilms: A History of Britain from Above. He is also the author of Fallen Glory: The Lives and Deaths of the World’s Greatest Lost Buildings, which was published to critical acclaim in 2015 and was shortlisted for the Saltire Non-Fiction Book of the Year Award. Scotland from the Sky is his first series for the BBC as writer and presenter.

Find out more about the Scotland from the Sky TV series on the BBC’s website: bbc.co.uk

Share this Post