A Guest Blog from Leyla Josephine

Leyla Josephine is a poet, performer, facilitator and award-winning theatre maker from Glasgow. Since December 2019 she has been the Schools Writer in Residence for Citizen, our long-term creative communities programme. Here, Leyla reflects on her time facilitating sessions with young people, showing how a play-focussed, collaborative approach to creativity can change their entire outlook on life.

In my workshops for Edinburgh International Book Festival, I encourage the children I work with to fail. And they do. In fact, they fail a lot. Horribly, catastrophically, magnificently.

In schools we teach children that there is a right or a wrong answer to the questions they are being asked and the tasks that they have to do. Up until then, there is an ambivalent attitude when it comes to young children mixing up ten and twelve, drawing six legs on a donkey or colouring the sky orange instead of blue. There is a slow incline in critique from Primary One to Sixth Year – from gentle nudges to the correct answer all the way to ‘if you don’t get this right you won’t get into university and you’ll never get a job’.

Right and wrong is a scary binary – if you are not right, you are wrong. Ouch. Even writing it down hurts. I never wore a dunce hat, but I could feel it weighing down on my head all through school while I walked down the corridors feeling like I didn’t belong there. I have to wonder what effect that being told you are ‘wrong’ has on children’s preparation for life.

"Life is a long list of failures"

I think of my own list of adult failures: the rejections from magazines, the unsuccessful funding applications, job interviews gone wrong, DIY left half done, laundry turned pink, houseplants left to die, cringey unfinished poems, sleeping audience members, broken relationships, bad behaviour. The list goes on and on and on. It trails off my laptop, out of my study, into my garden and all the way to Spain, where my failures sit smugly sipping on mojitos and laughing about what an ejiit I am.

Life is a long list of failures. There’s no denying it. But how we think about those failures and how we are taught to think about them is key. There is an opportunity in development years to shape the perspective we have on our failures. We should see failures are something that happens through trying, rather than something that defines us.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I know that there has to be a line. We still have to teach children that some things are absolute. Formulas that lead you to the correct answer, especially in subjects like spelling, maths and science. But my practice involves facilitating exercises that encourage children to learn from getting things wrong. Even if you don’t get something right first time, it’s not the end of the world – it doesn’t define you, or your future. It doesn’t mean you have to wear the invisible dunce hat. There is an emphasis on play rather than product.

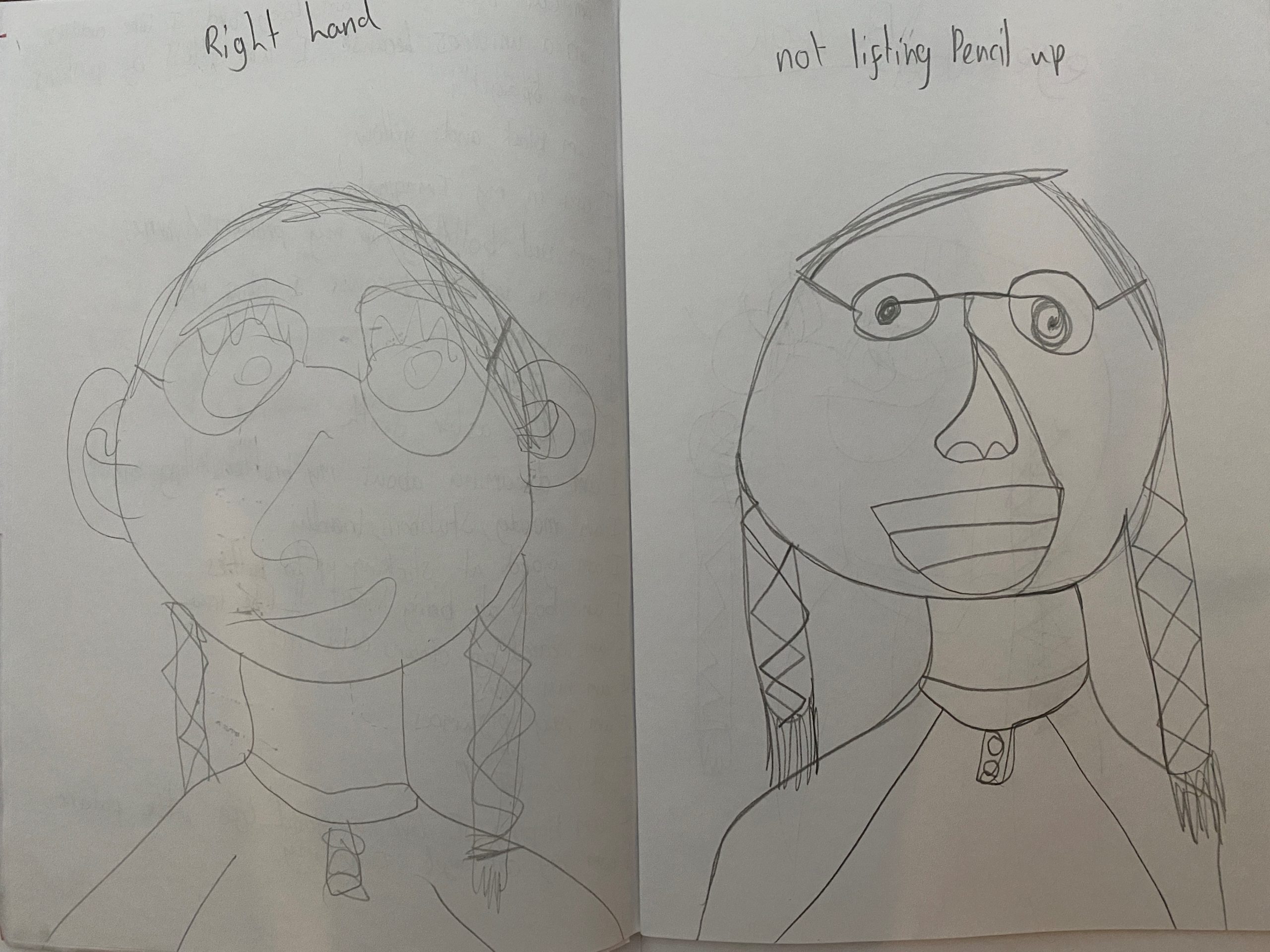

Example exercise: Self-portrait

Aims: Draw a terrible picture and be okay with it

Aims: Draw a terrible picture and be okay with it

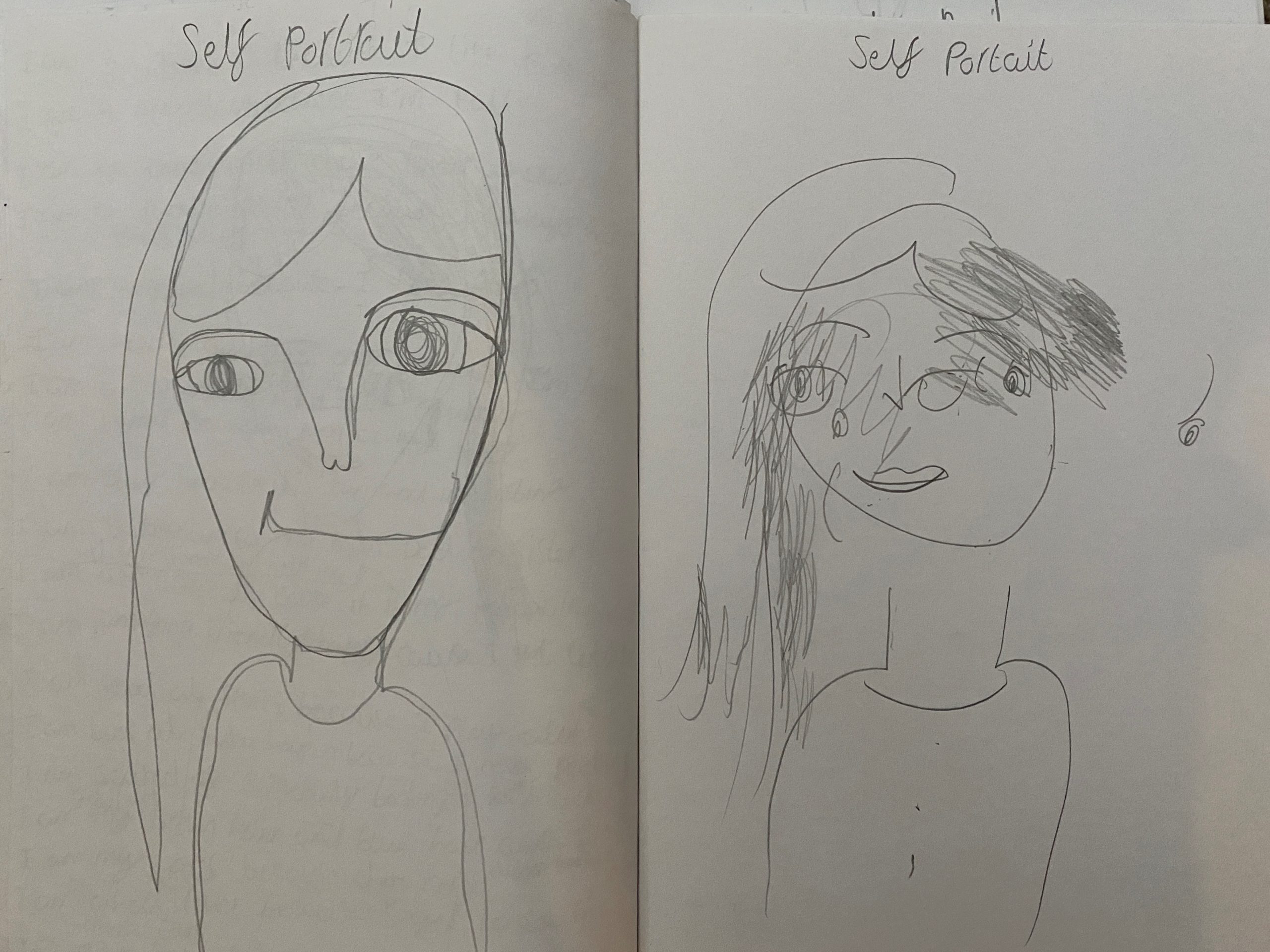

In my Citizen workshops, one of the exercises I ask children to do is to draw a self-portrait. When setting the task, I can see a division in the class straight away: half of them whoop and start whipping out their colouring pencils, the other half groan and press their faces into their elbow creases. These groups can be separated into two camps: ‘good’ at drawing, ‘bad’ at drawing.

As a side note – when asked to do this task, a lot of the children will reach for rulers. I had to ban rulers in one class, with some children going to massive lengths to sneak contraband ruler use when I wasn’t looking. A straight-line revolution against the authority! I like to call them the Ruler Defenders. I mean why would they need a ruler for drawing themselves? Am I, unknowingly, teaching a little collection of rectangles? Robots? Brutalist buildings? No, they want it to look precise and perfect, they want it to be the ‘right’ answer but there is not a ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ answer when it comes to creativity. Don’t even get me started on rubbers!

Once they’ve finished their portraits, I have another task for them. I know the Ruler Defenders are going to loathe it. They must do the same again, but this time they have to use the hand that they usually do not write with. One little instruction like this can totally disrupt the hierarchy of the class. The Ruler Defenders are in shock, unable to comprehend what it is I want from them, the other children that hate drawing suddenly perk up, feeling a little less disheartened. Once they finish this portrait, they must do it again but now without taking their hand off the page. As the exercise becomes more impossible to get ‘right’ it unpicks expectations and learned behaviours. The playing field is levelled – no longer is the task to get the most precise image but it is to follow the instructions. The final part of the task is to draw the portrait for a fourth time but now they must do it with their eyes shut. There can be no winners and hypothetically there should be no losers.

I don’t know exactly what pure joy sounds like, but I bet it comes pretty close to a group of children opening their eyes and seeing a terrible picture that they’ve drawn of themselves. The hysterics can get so loud sometimes that the teacher has to close the door. With belly laughs and elation, they gleefully show their pages to their peers, squealing at each other’s attempts. Someone’s got an arm coming out of their head, another has ears where there should be eyes, eyes where there should be ears, legs are in the top right corner of the page, it is chaos, it is wonderful.

But there is one child, (a suspected Ruler Defender) who isn’t laughing.

On her page there is a perfectly good, normal drawing, the nose is correctly placed, the hair is immaculate, eyes are parallel and beaming out, everything is carefully placed on the page. The drawer is disappointed, she’s misread the goal of this task. She is so used to praise for being excellent at drawing she couldn’t allow herself to fully close her eyes and let go. This happens all the time, it isn’t new, children think that getting things perfect without faltering is the only way to succeed, and who can blame them? It’s what they are taught.

In our capitalist society, we have adopted the American dream, success is the ultimate goal and failure isn’t an option. There is a long way to fall for those who are taught that failing is unacceptable. The people who can’t keep up get left behind and those who can develop an unhealthy relationship to failure. So, when failures inevitably happen, the world comes crashing down.

"Writing is about expressing yourself"

In the same way, there are huge barriers of self-consciousness when it comes to creative writing. People who think they can’t write often freeze when given a writing task. I know because it happens to me. I’m a dyslexic writer and sometimes I find myself completely paralysed by my worries over failing or looking stupid.

When asked to write something, young people will often flat out refuse to do so, because they think it’s just another way that they will be judged. They tell me they can’t do it, they don’t know what to write or they just don’t pick up a pen. It’s not just Primary age – I’ve seen it in high schools and I’ve seen it with adults. Writing is about expressing yourself, it’s about pen to paper. Spelling, grammar, literary skills are all great, but I would gladly sacrifice them all if it meant that young people didn’t feel crippled by expectation. I like to approach writing sessions without any expectations other than to play. When the pressure to be perfect is lifted, the pen touches the page and sometimes something is written. Maybe then, writing doesn’t seem so scary after all, the world didn’t end and there was no public humiliation.

By facilitating these creative tasks, I am setting up young people to fail. Or at least providing space for there to be no absolute answer. The children are encouraged to find pleasure and community through participation. If we introduced more play into our formal studies, then who knows what benefits it would have on academic performance? I bet there would be at least more inclination to try.

I’m concerned about young people’s self-worth and the tight rope it balances on. There is too much emphasis on nebulous assessments. But until institutional changes come, we have to think on our feet. By adding a few creative open goal exercises and tweaking our language on failure we can top putting perfectionism on a pedestal, preparing our children’s mental health for the world beyond school.

Creative education is a vital opportunity to change the framing surrounding failure. How many writers or artists we might lose if they think that they’re stupid for their spelling or because their drawing isn’t accurate? After all, the sky is orange sometimes, even if we have learned the ‘right’ answer is blue.

***

Citizen is part of Edinburgh International Book Festival On The Road. It is supported by players of People’s Postcode Lottery and through the PLACE Programme (funded by the Scottish Government, City of Edinburgh Council, and the Edinburgh Festivals, and supported and administered by Creative Scotland).

Share this Post